There is something magical about a 1950s ad: its bright colors, happy men and women, “better living through chemistry,” new car in the driveway, spotless kitchen, and homemaker model smiling with her appliances. These ads were not selling products; they were helping build what America thought it was and wanted to be. And, as with anything that is cultural, that identity had beautiful idealism and a disturbing cost.

Let’s ride back through time, stop by some real stories, and see what we can learn from those gleaming magazine pages today if we are producing, consuming, or simply thinking about identity.

Setting the Stage: Post-War America and the Rise of Advertising

After World War II, America changed rapidly. Soldiers returned home, the economy boomed, suburbs exploded, television became a home fixture, and there existed a kind of mass optimism: prosperity, technology, stability. Advertisers caught on. Products were not just functional; they were badges. Owning a new kitchen gadget, a shiny automobile, or the latest household gadget was not about convenience; it meant you were part of the new America.

Commercials of the era reflected that: dinner tables were surrounded by families, mothers in a dress, fathers coming home from work, and children playing in the backyard. The dominant discourse: “If you do things this way, you’re successful; you’re living the dream.” But since dreams by their very nature exclude, what was excluded was as important as what was included.

The Good: How 1950s Ads Inspired Identity, Unity, and Aspiration

Aspirations, Hope, and the Promise of Progress

Most Americans in the early 1950s had lived through the Great Depression, wartime rationing, and loss. The postwar advertising was powerful in offering hope. It said: Look, here’s what a family could have now: a newer car, a cleaner kitchen, more leisure time. The promise of “progress” was tied to high confidence in technology and consumption. For many, that was genuinely uplifting.

For example, appliance firms induced homemakers to buy new electric stoves, refrigerators, and washers. They were not just “appliances,” but symbols of freedom: less manual labor, more time for leisure or individual family time.

Shared Cultural Symbols and Unity

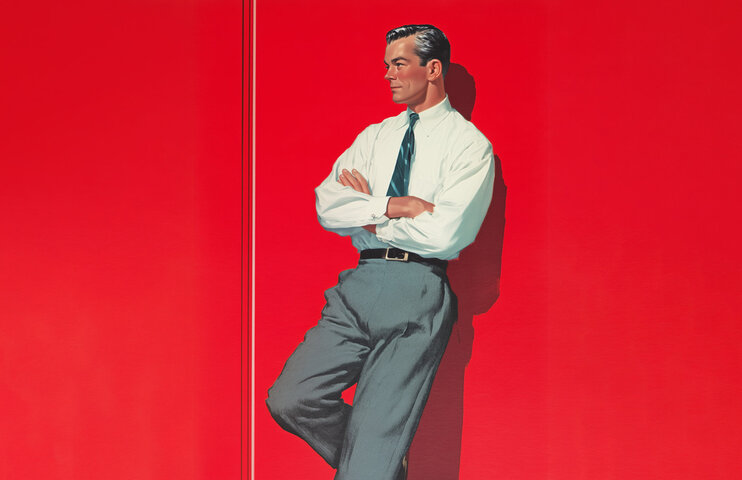

Commercials codified what mid-century “American” looked like: white picket fences, chrome cars, atom-age styling, well-manicured suburban lawns, a tie for dad, and a fresh dress for mom. Those images united many Americans around a shared aesthetic and set of values, white, middle-class Americans, at least. They created a normative image: this is the “good” life. That gave some people both a roadmap and a sense of belonging.

Even product jingles and slogans were a part of everyday life. Think about memorable advertising tunes people hummed along to; slogans you’d see in magazines or on TV, and feel like you were part of the national conversation. Ad agencies were early masters at creating identity as communal.

Innovation in Design, Storytelling, and Media

From print ads with hand-drawn illustrations to radio, to TV commercials (new and exciting), 50s advertisers experimented with everything. Their craft type, illustration, color usage, and modern design influenced visual culture for decades to follow. The legendary “Think Small” campaign for Volkswagen in 1959, for instance, broke the “bigger is better” convention and proved modesty, honesty, and humor could sell.

Even the movie posters of the day (like Rebel Without a Cause) added to youth identity and rebellion in the face of mere conformity, a visual storytelling lesson every poster designer could take a cue from today.

The Less Good: Exclusion, Idealism, and the Pressure to Conform

Whiteness, Exclusion, and Misrepresentation

Many 1950s commercials presented a story that was almost entirely white and middle-class. Minority groups, African-Americans, and non-“traditional” families were seldom seen or, if at all, represented stereotypically or in tokenistic fashion. The “American identity” being marketed was narrow. When individuals did not conform to the norm, they felt second-class or excluded.

When the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, the opposition claimed these representational gaps were not just a technicality; rather, they played on social hierarchies. This “ideal family” emblazoned from a shiny ad copy wasn’t one for all.

Rigid Gender Roles and Identity Pressure

1950s advertising was steeped in role-playing: women homemakers, men breadwinners. The owner of the fine mixer is satisfied; the owner of the car is smug; children admire both. The expectation that women get satisfaction from a lot of domestic labor, and that their identity is tied to appearance and comfort, is common in those ads. That pressure shaped identity for countless men and women. Many of them internalized the message, even as others quietly defied it.

Materialism, Consumer Debt, and the Assumption of Consumption

Identity in consumption promised so much that many began to believe “who I am” or “what I’m worth” is what I possess. Houses, cars, gizmos, all marketed as proof you belong, you’ve made it. Those who couldn’t afford them may feel pain in the disparity between the ideal and the real.

Real People, Real Stories

To place this in a human context, below are two stories of common Americans of the era (or speaking out subsequently in life) that detail how these advertisements shaped, and sometimes conflicted with, real identity.

- Marjorie, a teacher in Ohio, grew up wanting the perfect home. She recalled leafing through the pages of magazine designs where the kitchen was always clean, dinner was always hot, and kids were always smiling. As an adult, she gauged herself in part by whether her home “looked like that.” But when pressure from work, disease at home, or money cut into perfection, she felt guilty or ashamed because the advertising establishment convinced her that any imperfection was personal failure.

- James, a young Black entrepreneur in Chicago, bought products that had been advertised in Ebony and Jet (African-American-targeted magazines) because he could see in those ads a man like him, someone whose image was aspirational. At the same time, however, he noticed the sharp contrast between those specially targeted ads and the other mainstream advertisements that almost totally shied away from people of his identity. It made him keen-eyed and eventually critical of identity construction in the broader advertising culture.

Lessons and Takeaways for Today

- For creators and marketers: Pay attention to the fact that the images you choose (who you’re including, who you’re excluding) carry weight. In building brand identity, think beyond the buy: how do you represent different kinds of people?

- For designers and illustrators: Look at historic ad design typography, color scheme, and layout. Sometimes, creating visuals with a poster creator captures that same vintage energy, combining nostalgic style with a fresh, contemporary twist.

- For consumers: Think about how advertisements influence your notions of success, beauty, and family. Knowledge sets you free from unrealistic comparisons.

- For parents and educators: Show the next generations how advertising operates. Collect old advertisements and discuss what they care about, what’s absent, and whose voices are missing.

How This Still Matters

Retro aesthetic pervades everything from diner-sponsored coffee shops to Instagram effects. When we view that imagery, we’re also re-evoking identity: simplicity, optimism, pastel colors, chrome vehicles.

Most of the brand messages still rely on imaged imagery, calling on the 1950s model of “ideal success” and “ideal home.” Recognizing that heritage gives us a richer, more varied story now.

FAQs

1. Why were 1950s ads so influential in shaping culture?

Because advertising was expanding into new media like TV and radio, it reached millions of homes simultaneously. Its repeated imagery and messages created shared ideals of success, family, and beauty.

2. How did 1950s ads affect gender roles?

They reinforced strict roles of men as breadwinners and women as homemakers, which became cultural expectations for decades.

3. Were there any positive aspects to 1950s advertising?

Yes. Ads reflected optimism, innovation, and creative visual storytelling that helped define the golden age of design and mass media.

4. What can modern advertisers learn from 1950s campaigns?

Embrace storytelling and aesthetics, but avoid exclusionary narratives. Balance nostalgia with inclusivity and authenticity.

5. Why does this topic still matter today?

Because the patterns of identity creation in ads, inclusion, aspiration, and materialism still shape how brands and consumers interact today.